I briefly describe five focal areas of my research group below. Full text publications are available here.

- evolutionary medicine

- heart disease

- diabetes

- inequality & psychosocial determinants of health

- indigenous health

Cardiometabolic disease in evolutionary context. To what extent are chronic, non-communicable diseases such as atherosclerosis, diabetes and Alzheimer's disease novel epidemiological challenges? It is often assumed that adults in small-scale societies are free of these modern diseases, but most evidence to date is indirect, relying on traditional risk factors that might operate differently in non-urban environments. For example, we found that neither high inflammation nor low HDL cholesterol were associated with heart disease amongst Tsimane Amerindians. Exciting opportunities to better understand the etiology and epidemiology of chronic diseases are available working in non-traditional settings, such as small-scale societies often experiencing rapid lifestyle change. First, more direct measures employing biomarkers and modern technologies (e.g. EKGs, CT scanners) can help inform our understanding of chronic diseases. Second, incipient increases in heart disease and diabetes incidence amongst small-scale societies today provides an opportunity to study the relative contribution of genetics and lifestyle factors prospectively. The variable experience of inequality, discrimination and psychosocial factors amid socioeconomic change is an important target of study.

- host-parasite dynamics

- pathogens and life history trade-offs

- inflammation

Role of pathogens on the human life course. ‘Hygiene’ and ‘Old Friends’ hypotheses propose that reductions in the abundance and diversity of microbial and parasitic exposures are responsible for a variety of immune-mediated ailments today. An evolved history defined by exposure to diverse microbiota would have had broad effects on immune function and energy allocation to growth and reproduction. Lab members have studied the effects of intestinal helminths on immune development and co-infection risk with other pathogens, trade-offs with growth, and impacts on fertility and energetic expenditure. Current studies explore the effects of worms on inflammation, insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. Long-evolved strategies of helminths include drawing metabolic resources from their host, including blood lipids and glucose, and modulating immune function towards greater anti-inflammatory activity—alterations that could possibly slow atheroma progression. Distilling the effects of their absence in modern environments alongside obesogenic diets and physical inactivity are being actively researched.

- human life history evolution

- intergenerational transfers and sociality

- risk buffering

- chimpanzee-human demography

- post-reproductive longevity

- social learning of subsistence

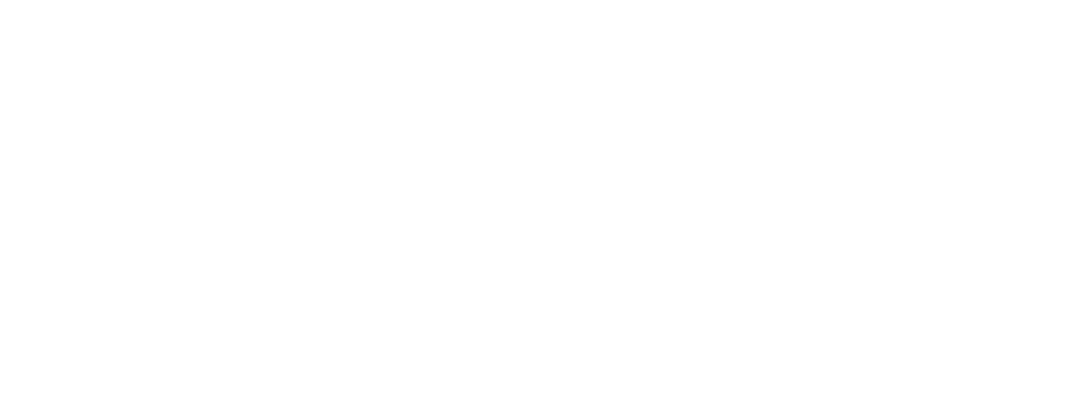

Human life history evolution. Extended juvenile growth and development, encephalized brains and slow foraging skill acquisition, long post-reproductive life and multi-generational resource transfers are hallmark features of the evolved human life history. Developing and testing competing models of life history evolution requires creative approaches to both data and theory. Detailed ecological and demographic study of hunter-gatherers and other small-scale subsistence populations, nonhuman primates, and other species analogues (e.g. killer whales) are necessary. One project involves exploring fitness benefits of postreproductive adults, not only in terms of food production, but also coresidence patterns, advice, storytelling, and conflict mediation. Another models the conditions leading to intergenerational transfers not only of material resources, but of information (i.e. instruction). Another goal is to model how a human foraging ecology might lead to the types of sharing norms we find cross-culturally, and the cost-benefit logic underlying a seven decade lifespan.

- modernization

- migration and diffusion of ideas

- personality

- risk buffering and socioeconomic change

- outgroup tolerance and identity expansion

- fertility decline

- time preference

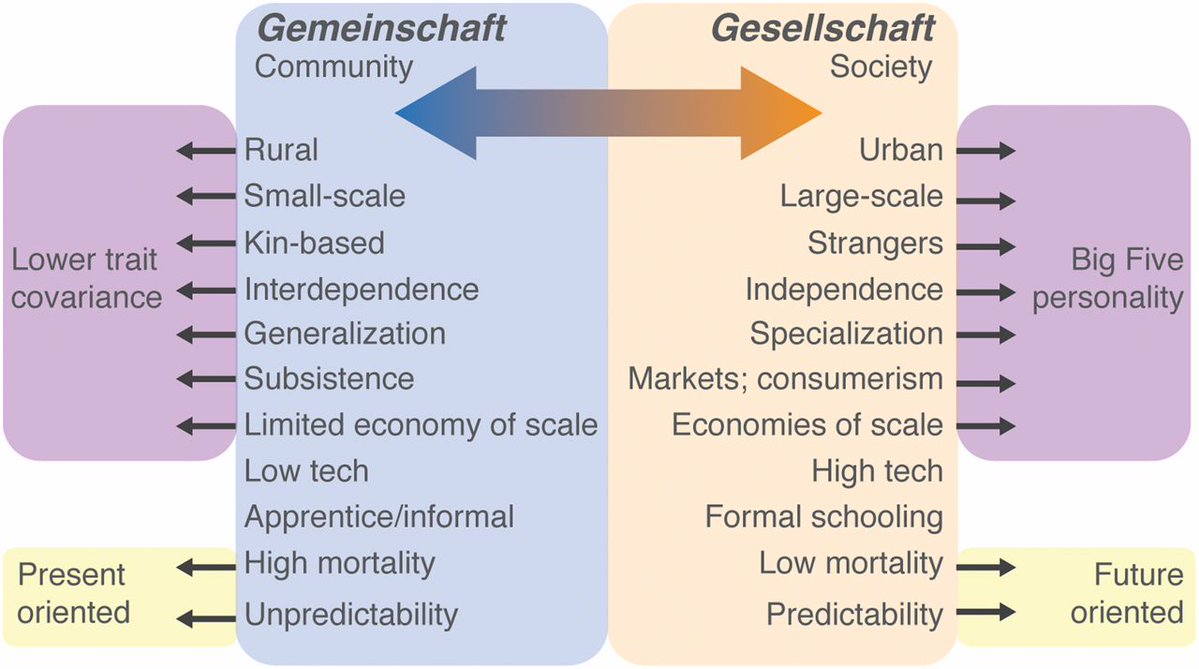

‘Modernization’ and social ecology. Over the past two centuries, many have theorized about how the “Great Transformation” of traditional populations to a “Market Society” alters the social and economic landscape and human mentalities. Most small-scale populations today have been experiencing rapid socioeconomic and cultural change amid globalizing forces; it is often misleading to ignore or simplify ethnographic descriptions by relying mainly on the typical anthropological subsistence categories (e.g. horticulturalist), and also a disservice toward understanding decision-making amid the increasing complexity of modern life. These circumstances around the world are natural laboratories for exploring the effects of modernization on behavior, psychology and health—the separate impacts of schooling, technology, market transactions in an increasingly monetized economy, interactions with strangers, inequality and discrimination. Current lab studies focus on how changing labor markets impact fertility-related decision-making and perceptions of child investment costs, how privatization and self-reliance affect risk sharing networks and social buffering patterns, how growing cosmopolitanism and shifting networks affect tolerance and interest in strangers, how identity expansion shapes views on corruption, and how reductions in environmental harshness promote psychological self-efficacy in ways that increase the motivation to seek treatment for common ailments. We also study how economic specialization and social complexity can shape the expression of multi-dimensional personality structure.

- gendered health disparities

- costs of reproduction

- social status and political leadership

Gendered inequalities in health, social status and well-being. Males at most ages exhibit higher mortality than females, yet morbidity rates for many conditions are higher among females – though the extent of sex differences varies among populations and over time. To what extent do costs associated with reproduction affect women (and men), especially in high fertility contexts with short interbirth intervals and intensive breastfeeding? Disposable soma theory suggests that intense investments in reproduction should trade-off against investments in somatic maintenance and survival under energetic constraints. Current projects have tested this idea by examining effects of parity and pace of reproduction on maternal nutritional status, bone mineral density, and gynecological morbidity. In natural fertility populations, high fertility can be a source of status and other benefits, but also an obstacle, especially under changing conditions. As autonomy and political clout of women shift during socioeconomic and cultural transformation, women’s and men’s changing influence can affect their own health and that of their families in disparate ways. These topics are currently being explored in Bolivia and Morocco.